How to draw God: Parshat Vayetzeh

Vayetzeh begins in the footsteps of Yaakov’s Journey, leaving Beer Sheva on his way to Haran. Yaacov finds a spot he is seemingly pleased with, and decides to sleep there as the sun begins to set. He lays his head on a stone (or, as the Midrash famously tells us, stones) and begins to dream. This story in particular soon became perhaps one of Art History’s, certainly Western Art History’s, most depicted dream-image.

וַֽיַּחֲלֹ֗ם וְהִנֵּ֤ה סֻלָּם֙ מֻצָּ֣ב אַ֔רְצָה וְרֹאשׁ֖וֹ מַגִּ֣יעַ הַשָּׁמָ֑יְמָה וְהִנֵּה֙ מַלְאֲכֵ֣י אֱלֹהִ֔ים עֹלִ֥ים וְיֹרְדִ֖ים בּֽוֹ׃

He had a dream; a stairway* was set on the ground and its top reached to the sky, and messengers of God were going up and down on it.

וְהִנֵּ֨ה יְהֹוָ֜ה נִצָּ֣ב עָלָיו֮ וַיֹּאמַר֒ אֲנִ֣י יְהֹוָ֗ה אֱלֹהֵי֙ אַבְרָהָ֣ם אָבִ֔יךָ וֵאלֹהֵ֖י יִצְחָ֑ק הָאָ֗רֶץ אֲשֶׁ֤ר אַתָּה֙ שֹׁכֵ֣ב עָלֶ֔יהָ לְךָ֥ אֶתְּנֶ֖נָּה וּלְזַרְעֶֽךָ׃

And standing beside him was יהוה, who said, “I am יהוה, the God of your father Abraham’s [house] and the God of Isaac’s [house]: the ground on which you are lying I will assign to you and to your offspring.

וְהָיָ֤ה זַרְעֲךָ֙ כַּעֲפַ֣ר הָאָ֔רֶץ וּפָרַצְתָּ֛ יָ֥מָּה וָקֵ֖דְמָה וְצָפֹ֣נָה וָנֶ֑גְבָּה וְנִבְרְכ֥וּ בְךָ֛ כׇּל־מִשְׁפְּחֹ֥ת הָאֲדָמָ֖ה וּבְזַרְעֶֽךָ׃

Your descendants shall be as the dust of the earth; you shall spread out to the west and to the east, to the north and to the south. All the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you and your descendants.

וְהִנֵּ֨ה אָנֹכִ֜י עִמָּ֗ךְ וּשְׁמַרְתִּ֙יךָ֙ בְּכֹ֣ל אֲשֶׁר־תֵּלֵ֔ךְ וַהֲשִׁ֣בֹתִ֔יךָ אֶל־הָאֲדָמָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את כִּ֚י לֹ֣א אֶֽעֱזׇבְךָ֔ עַ֚ד אֲשֶׁ֣ר אִם־עָשִׂ֔יתִי אֵ֥ת אֲשֶׁר־דִּבַּ֖רְתִּי לָֽךְ׃

Remember, I am with you: I will protect you wherever you go and will bring you back to this land. I will not leave you until I have done what I have promised you.”

Yaakov wakes up from the dream, and goes on to continue his journey. Once adapted into the Christian tradition, this scene, one of much grandeur within spiritual encounter, inspired the works of incredible European masters of the Renaissance, including Giorgio Vasari II (Italian, 1511-1574), Raphael Sanzio (Italia, 1483−1520), and many more. Although, these masterpieces depict Jacob’s dream so differently than our own tradition.

The Rambam (Hilhot Avodas Kochavim Ch. 3:10-11) prohibits drawing angels and heavenly deities altogether, but allows humans two-dimensionally, and other living things even when they are sculptures. The Kesef Mishnah there says that Rambam is of the opinion that the only exception that can be made is for pedagogical purposes. He also says that Rabbi Isaac Alfasi, or the Rif, espouses this view. (The Tur codifies the Rif's opinion as such.)

The Shulchan Aruch (Yoreh Deyah 141) permits the drawing of angels, man and other living things, but prohibits any image of the sun, moon, or stars that is not for pedagogical purposes. The Tur agrees, although he even allows the sun and moon and the like to be sculpted if made for the public.

My most vivid visual memories of Yaakov’s ladder while being a child within the early American Jewish educational system is, unsurprisingly, always a christian representation. Their baroque and undersaturated drawings of the dream almost always contain images of God, something that all halachik Interpretations agree to prohibit. One can argue whether angels, deities, or humans may be halachikally permitted for pedagogical purposes, but nobody can make a halachik case for painting God himself, for any purpose that is.

Creatives often see censorship as meaningless blocks on creativity, which I usually agree with, but taking a look at other representations of this scene perhaps points to more possibilities within the realm of the limited.

Marc Chagall grew up in the small Hasidic town of Vitebsk, where drawing any creation made by God (anything) was already a violation of the Second Commandment. Interestingly enough, Chagall filled his void of images with creating some of the most celebrated and imperative images of Jewish Life ever made. His paintings never include images of God, as he’s mentioned multiple times in his autobiography, that the Torah does not allow creating any image of God. Instead, his pieces are deeply profound colorful meditations of Tanakh scenes, images of Jewish life and folklore.

If you recently came to Havurah’s last gallery show: EMANATIONS: A Gallery Night of Contemporary Jewish Portraiture, you’d understand the deep theological intentions of how to even define images of God:

“In the story of Shemot, when God calls upon Moshe to construct a sanctuary for His spirit to dwell among the people of Israel, Moshe instructs Bezalel to build an arch, Kelim, and a Mishkan. Several explanations are given for why Bezalel is chosen to build the Mishkan: his wisdom; his intellect; his understanding of creation. In Talmud Bavli, Rav Yehudah points to Bezalel’s ability to “combine the letters that were used to make the Heavens and Earth” [Berakhot 55a:12-13], or in other words, to attempt an act of formation in the physical world that parallels creation itself. Bezalel, confused by Moshe’s instructions, replies that one should first build a house and then fill it with things, or else “where do I place the vessels that I am making?” [Rashi Exodus 35:22]. Here we see Bezalel’s intuition that the universe is ordered in a certain way: Divine energy needs a physical home here on earth. The Gemara expounds: Moshe answered, “What you have said is indeed the way I heard it. You are just like your name BTZAL-EL, In the shadow of God.”

-Lindsay Leboyer, Havurah Chair of Art

Just as the world we live in is a realm of vessels containing endless light, so too are the images we create in this world. The very act of creating art, which mimics actual creation, allows us to realize the beauty of capturing forms of Godliness in all the lines, forms, and colors we choose to include in our images. Our Halachik prohibition of drawing God in any concrete visualization not only allows us to experience Hashem in nearly every aspect of our lives, but also gives us the ability to critically create.

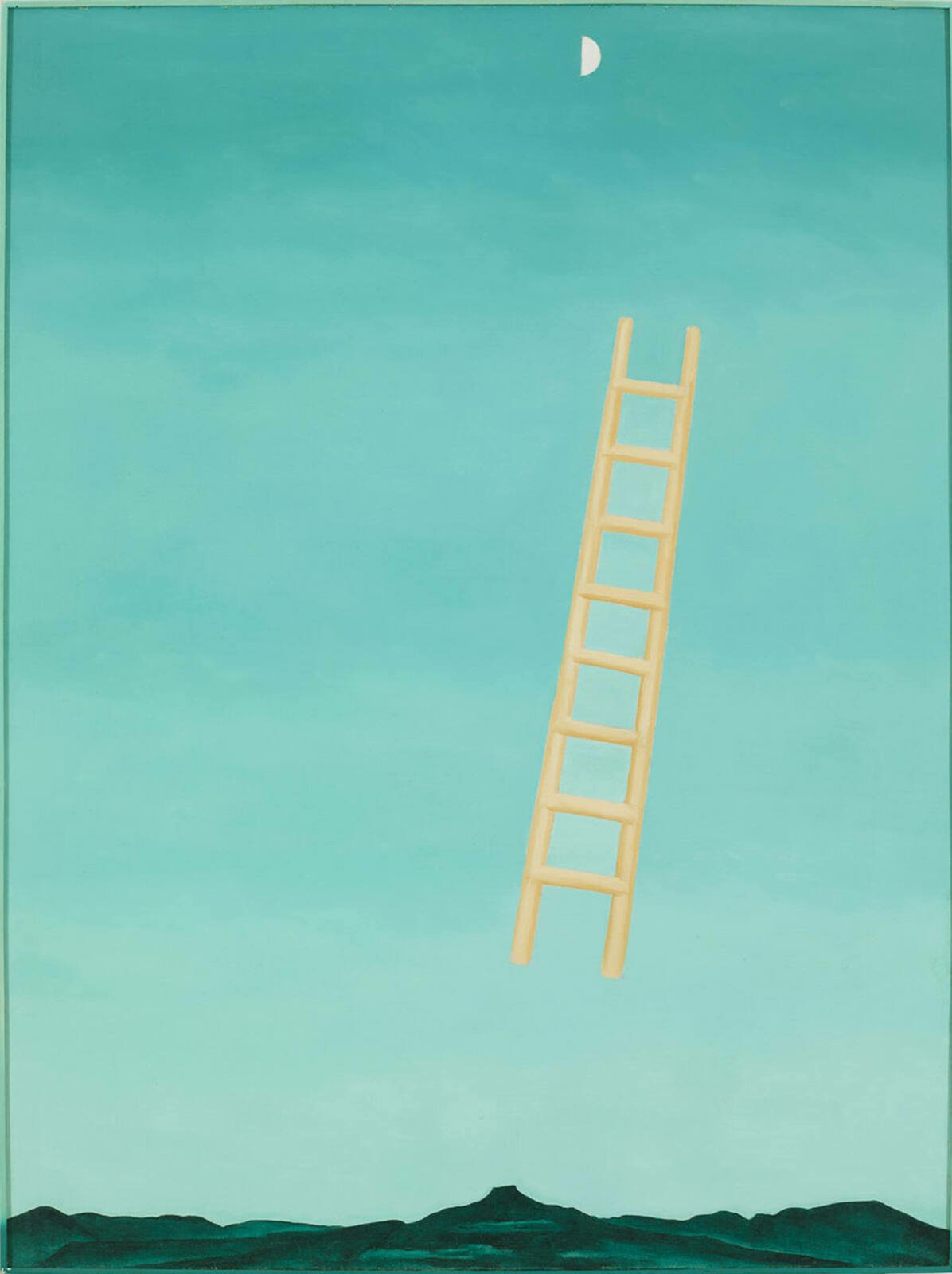

Last week I found myself on the Whitney’s virtual collection, spending what felt like hours staring at Ladder to the Moon. (Georgia O'Keeffe 1958) The painting is said to be an interpretation of items found on the roof of her own house, although I saw something else in between the lines.

Ladder to the Moon, Georgia O'Keeffe 1958